Map Reduce - Jeff Dean

Disclaimer: These notes were taken while attending the COL 733:Cloud Computing course at IIT Delhi and the 6.5840:Distributed Systems course offered at MIT by Robert Morris.

Overview

Multi-hour computations on multi-terabyte data sets. e.g. build search index, or sort, or analyze the structure of web

only practical with 1000s of computers. applications not written by distributed systems experts.

Goal

Build a framework for non-specialist programmers to write and run giant distributed computations, programmer just defines the Map and Reduce functions. often fairly simple sequential code. MapReduce takes care of, and hides all the aspects of distribution.

Abstract View

It starts by assuming there is some Input and this input is split up into different bunch of files and chunks

input is (already) split into M files

graph LR

subgraph Inputs

A[Input1] --> |a,1| Map1

A --> |b,1| Map1

B[Input2] --> |b,1| Map2

C[Input3] --> |a,1| Map3

C --> |c,1| Map3

end

subgraph Mappers

Map1 --> |a,1| S1[a,1]

Map1 --> |b,1| S2[b,1]

Map2 --> |b,1| S2[b,1]

Map3 --> |a,1| S1[a,1]

Map3 --> |c,1| S3[c,1]

end

subgraph Reducers

S1 --> |a,2| ReduceA[a,2]

S2 --> |b,2| ReduceB[b,2]

S3 --> |c,1| ReduceC[c,1]

end

we can already see here there is some parallelism going on here. so we can run the maps in parallel. The Map funciton takes in a input and produces an output The function takes the file as an input and outputs a list of key value pairs MR calls Map() for each input file, produces set of k2,v2 “intermediate” data

each Map() and Reduce() is called a “task”, the whole computation is called a job

MR gathers all intermediate v2’s for a given k2, and passes each key + values to a Reduce call, final output is set of <k2,v3> pairs from Reduce()s

Example: word count input is thousands of text files Map(k, v) split v into words for each word w emit(w, “1”) Reduce(k, v) emit(len(v))

MAP() for word count what the map(k,v) for the word count would do is

- Split the k(file name), and v(is the content of this maps input file)

- Split V into words

- for each word emit(k,v), emit takes two args, only map can make calls to emit(word, value)

REDUCE() for wordcount

- Reduce(k,v) is called with the key that its responsible for and vector of all the values that the maps produced.

- has its own emitter that takes a value to be emitted as the final output for this key –> emit(len(v)) emits the length of the vector

the output of the Reduce function can be used as the input for the next Map function..

MapReduce framework is great for working with algorithms that are easily expressable as a map.

Maps are independent and they just look at their arguments since they are pure functional funcitons.

Q. In the paper they distinguish between Mappers and map() and reducers and reduce(), i guess they are just the processes that are running the map(), what are the things you would consider are more important to distinguish b/w the processess and the map reduce()?

from the programmers pov its just about map and reduce but from our point of view its going to be about workere processess and the workere servers that are part of the map reduce framework that call the map () reduce ()

Q. When you call emit where does happens to the data, does it emit locally? and where do the functions run?

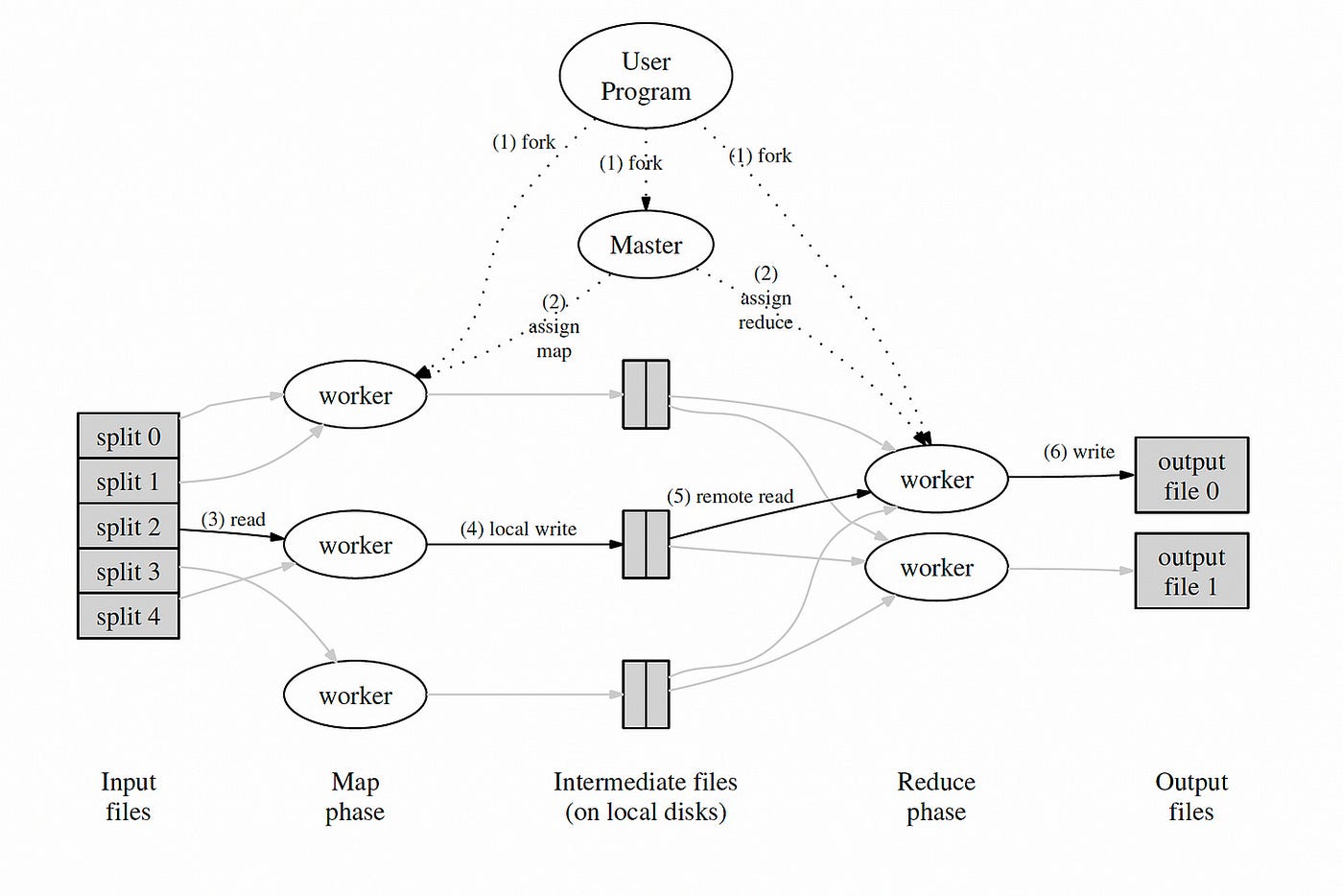

A. First where the stuff runs. see fig 1 in paper, underneath we have big collection of servers we call them workers there is also a master server thats organizing this computation. The master server knows that there’s some number of input files. and it farms out invocations of map to different workers. Its the worker that implements the map function on the input file and then everytime the map calls emit, the worker process will write this to files on the local disk.

Map emits produces files on the map workers local disk that are accumulating all the keys and values produced by the maps run on that worker.

At the end of the map phase, all those worker machines that have all the output of some input file, then the MapReduce works arrange to move the data to where its going to be needed by the reducers.

So the Reduce is going to need all the map output that mentioned a certain key(a), so before we run the reduce function, the mapReduce worker will have to go to the master node and the master node has the path to all the workers that have the key(a) in their intermediate local storage and then from there the reducer worker will go to the map worker and take the key(a).

Reduce emit, it writes the output to a file in a cluster of files service.

The input and output are both files. because we want the flexibility to read any piece of input on any worker server that means we need a network file system to store the input data. Read GFS paper(GOOGLE FILE SYSTEM)

GFS if you store any big file on it will automatically split it and store it across a lot of servers in 64Megabyte chunks.

Is the MapReduce and the GFS running on different set of machines. like these map workers might have to read from a different machine. What is the arrow mean in Input –> Map() The arrow represents, the map reduce worker may have to talk across the network to the correct GFS server that store its part of the input and fetch it over the network to the map function machine. thats a lot of communication.

Mapreduce BottleNeck: Network throughput

MapReduce scales well:

N “worker” computers get you Nx throughput.

Maps()s can run in parallel, since they don’t interact. Same for Reduce()s. So you can get more throughput by buying more computers.

MapReduce hides many details:

- sending app code to servers

- tracking which tasks are done

- moving data from Maps to Reduces

- balancing load over servers

- recovering from failures

However, MapReduce limits what apps can do:

- No interaction or state (other than via intermediate output).

- No iteration, no multi-stage pipelines.

- No real-time or streaming processing.

Input and output are stored on the GFS cluster file system MR needs huge parallel input and output throughput. GFS splits files over many servers, in 64 MB chunks

Maps read in parallel, Reduces write in parallel

GFS also replicates each file on 2 or 3 servers Having GFS is a big win for MapReduce

What will likely limit the performance?

We care since that’s the thing to optimize. CPU? memory? disk? network? In 2004 authors were limited by network capacity.

What does MR send over the network?

Maps read input from GFS. Reduces read Map output.

Can be as large as input, e.g. for sorting. Reduces write output files to GFS.

graph TD

subgraph Network

S1[Server 1]

S2[Server 2]

S3[Server 3]

S4[Server 4]

S5[Server 5]

SW1[Switch 1]

SW2[Switch 2]

SW3[Switch 3]

SW4[Switch 4]

SW5[Switch 5]

SW6[Switch 6]

SW1 --> SW2

SW1 --> SW3

SW2 --> SW4

SW2 --> SW5

SW3 --> SW6

SW4 --> S1

SW4 --> S2

SW5 --> S3

SW5 --> S4

SW6 --> S5

end

In MR’s all-to-all shuffle, half of traffic goes through root switch. Paper’s root switch: 100 to 200 gigabits/second, total 1800 machines, so 55 megabits/second/machine. 55 is small, e.g. much less than disk or RAM speed. Today: networks and root switches are much faster relative to CPU/disk.

Some details from the above image:

one master, that hands out tasks to workers and remembers progress.

- master gives Map tasks to workers until all Maps complete Maps write output (intermediate data) to local disk Maps split output, by hash, into one file per Reduce task

- after all Maps have finished, master hands out Reduce tasks each Reduce fetches its intermediate output from (all) Map workers each Reduce task writes a separate output file on GFS

How does MR minimize network use?

Master tries to run each Map task on GFS server that stores its input. All computers run both GFS and MR workers, So input is read from local disk (via GFS), not over network.

- Intermediate data goes over network just once.

- Map worker writes to local disk.

- Reduce workers read directly from Map workers, not via GFS.

Intermediate data partitioned into files holding many keys.

- R is much smaller than the number of keys.

- Big network transfers are more efficient.

How does MR get good load balance?

Wasteful and slow if N-1 servers have to wait for 1 slow server to finish.

But some tasks likely take longer than others.

Solution: many more tasks than workers.

- Master hands out new tasks to workers who finish previous tasks.

- So no task is so big it dominates completion time (hopefully).

- So if the task is too large the master will break the large task and distribute it to workers that are fast and become ideal.

- So faster servers do more tasks than slower ones, finish abt the same time.

What about fault tolerance?

I.e. what if a worker crashes during a MR job?

We want to completely hide failures from the application programmer!

Does MR have to re-run the whole job from the beginning?

Why not?

MR re-runs just the failed Map()s and Reduce()s.

Suppose MR runs a Map twice, one Reduce sees first run’s output, another Reduce sees the second run’s output?

Correctness requires re-execution to yield exactly the same output. So Map and Reduce must be pure deterministic functions:

- they are only allowed to look at their arguments.

- no state, no file I/O, no interaction, no external communication.

What if you wanted to allow non-functional Map or Reduce?

Worker failure would require whole job to be re-executed, or you’d need to create synchronized global checkpoints.

Details of worker crash recovery:

-

Map worker crashes: master notices worker no longer responds to pings, master knows which Map tasks it ran on that worker those tasks’ intermediate output is now lost, must be re-created master tells other workers to run those tasks 1can omit re-running if Reduces already fetched the intermediate data.

- Reduce worker crashes.

- finished tasks are OK – stored in GFS, with replicas.

- master re-starts worker’s unfinished tasks on other workers.

Other failures/problems:

### What if the master gives two workers the same Map() task?

- perhaps the master incorrectly thinks one worker died.

- it will tell Reduce workers about only one of them.

### What if the master gives two workers the same Reduce() task?

- they will both try to write the same output file on GFS!

- atomic GFS rename prevents mixing; one complete file will be visible.

### What if a single worker is very slow – a “straggler”?

- perhaps due to flakey hardware.

- master starts a second copy of last few tasks.

### What if a worker computes incorrect output, due to broken h/w or s/w?

- too bad! MR assumes “fail-stop” CPUs and software.

### What if the master crashes?

Current status?

- Hugely influential (Hadoop, Spark, &c).

- Probably no longer in use at Google.

- Replaced by Flume / FlumeJava (see paper by Chambers et al).

- GFS replaced by Colossus (no good description), and BigTable.

Conclusion

MapReduce single-handedly made big cluster computation popular.

- Not the most efficient or flexible.

- Scales well.

- Easy to program – failures and data movement are hidden. These were good trade-offs in practice.

Comments powered by Disqus.